Synopsis

Paul Gauguin is one of the most significant French artists to be initially schooled in Impressionism, but who broke away from its fascination with the everyday world to pioneer a new style of painting broadly referred to as Symbolism. As the Impressionist movement was culminating in the late 1880s, Gauguin experimented with new color theories and semi-decorative approaches to painting. He famously worked one summer in an intensely colorful style alongside Vincent Van Gogh in the south of France, before turning his back entirely on Western society. He had already abandoned a former life as a stockbroker by the time he began traveling regularly to the south Pacific in the early 1890s, where he developed a new style that married everyday observation with mystical symbolism, a style strongly influenced by the popular, so-called “primitive” arts of Africa, Asia, and French Polynesia. Gauguin’s rejection of his European family, society, and the Paris art world for a life apart, in the land of the “Other,” has come to serve as a romantic example of the artist-as-wandering-mystic.

Key Ideas

After mastering Impressionist methods for depicting the optical experience of nature, Gauguin studied religious communities in rural Brittany and various landscapes in the Caribbean, while also educating himself in the latest French ideas on the subject of painting and color theory (the latter much influenced by recent scientific study into the various, unstable processes of visual perception). This background contributed to Gauguin’s gradual development of a new kind of “synthetic” painting, one that functions as a symbolic, rather than a merely documentary, or mirror-like, reflection of reality.

Seeking the kind of direct relationship to the natural world that he witnessed in various communities of French Polynesia and other non-western cultures, Gauguin treated his painting as a philosophical meditation on the ultimate meaning of human existence, as well as the possibility of religious fulfillment and answers on how to live closer to nature.

Gauguin was one of the key participants during the last decades of the 19th century in a European cultural movement that has since come to be referred to as Primitivism. The term denotes the Western fascination for less industrially-developed cultures, and the romantic notion that non-Western people might be more genuinely spiritual, or closer in touch with elemental forces of the cosmos, than their comparatively “artificial” European and American counterparts.

Once he had virtually abandoned his wife, his four children, and the entire art world of Europe, Gauguin’s name and work became synonymous, as they remain to this day, with the idea of ultimate artistic freedom, or the complete liberation of the creative individual from one’s original cultural moorings.

Most Important Art

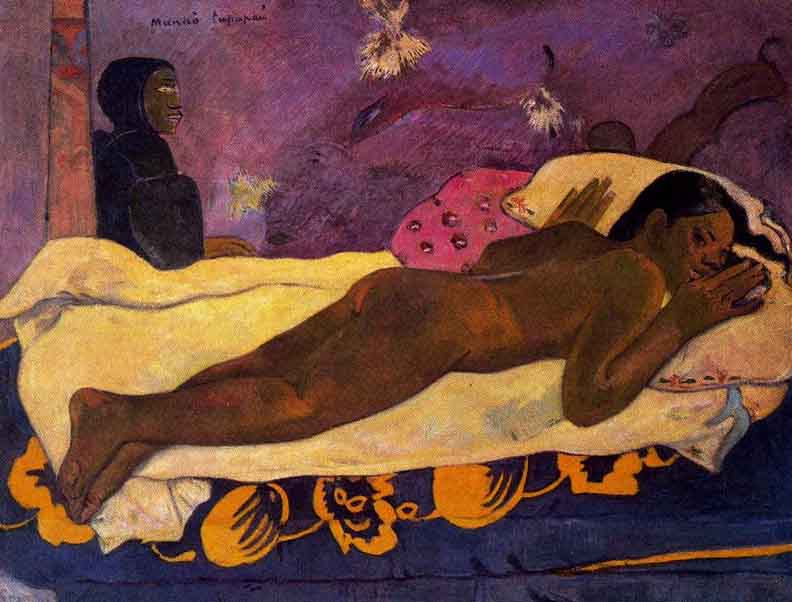

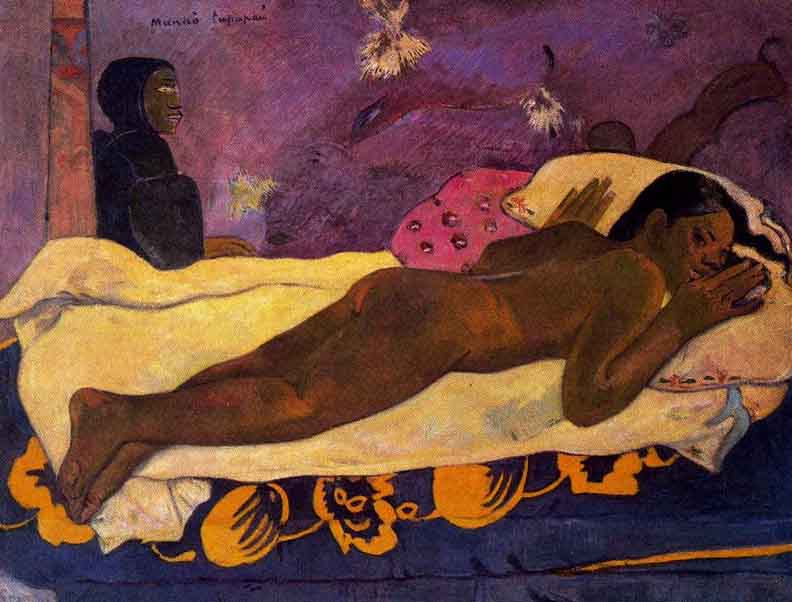

Manao Tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch) (1892)

One of Gauguin’s most famous works,

Manao Tupapau is an excellent example of how Gauguin relished combining the ordinary with suggestions of the extraordinary in a single canvas, thus leaving all final interpretation open to debate. As he relates in a period diary, the actual scenario was inspired by his return home late one night and finding his wife, depicted here naked in the tropical heat, suddenly startled by his strike of a match in the all-enveloping darkness. Gauguin captures the luminous, unreal look of the sub-equatorial interior, here decorated by floral textiles, or batiks, along with other earthy materials, all suddenly illuminated by a momentary chemical combustion. At the same time, Gauguin introduces a ghostly depiction of a “watching” female spirit, seemingly harmless, at the foot of the bed, a direct reference to a local folklore describing how such spirits roam the night and forever share the world of the living.

This same painting also illustrates well how Gauguin remained forever a child of the 19th century, while nonetheless functioning as a bellwether, or beacon, to a younger generation. Most of his work remained rooted in the natural world around him, a legacy of his roots in Impressionism. But in some instances, Guaguin even speaks to the work of a former master, such as in this work, which for many eyes continues a precedent of the everyday, un-idealized nude set by Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). Yet Gauguin’s work finally suggests, like that of his even more Symbolist contemporaries Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau (both were more closely aligned than Gauguin with French Symbolist poetry of the day), that underneath the world of “rock solid” appearances lies a parallel realm of eternal mystery, spiritual import, and poetic suggestion.

Oil on canvas – The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

More Art Works